Lockdowns have worked before, but can we expect the new one to do the same?

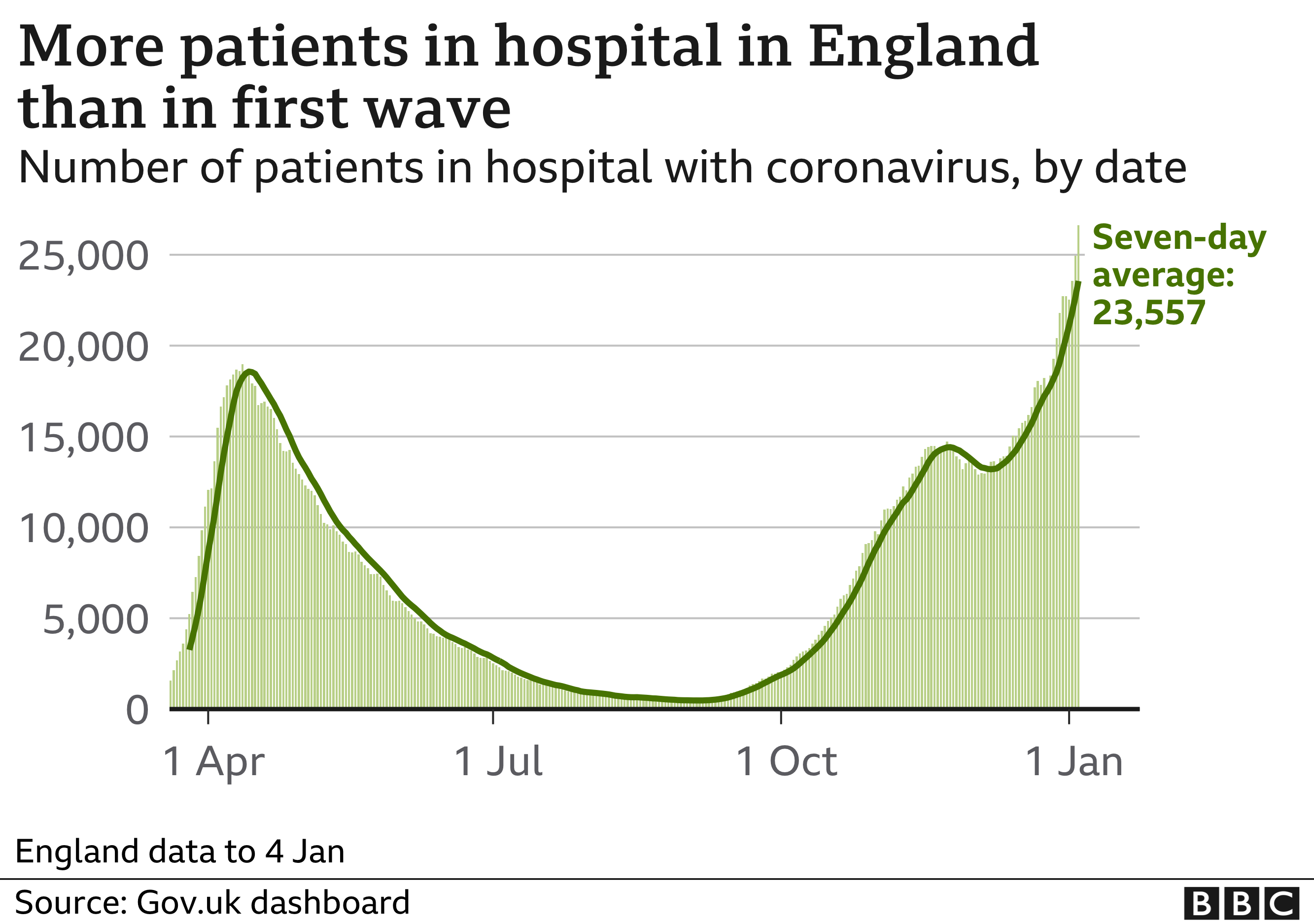

It feels like we are back in March or April last year when the strict controls on all our lives led to a fairly quick decline in levels of coronavirus.

But one of the crucial differences this time is the new variant, which is thought to spread between 50 and 70% faster than previous forms of the virus.

Experts warn there are now no guarantees that lockdown will be enough to bring the variant under control.

"It still would not have been easy, but it would have been a much easier situation if it had not been for the new variant," Prof Neil Ferguson, from Imperial College London, told Inside Health.

"That really pushes the bounds of our ability to control the spread of the virus, even with measures that were previously relatively quite effective."

The coronavirus spreads when we come into contact with each other so moving classrooms online, telling people to stay at home and closing shops breaks many of those opportunities for human contact.

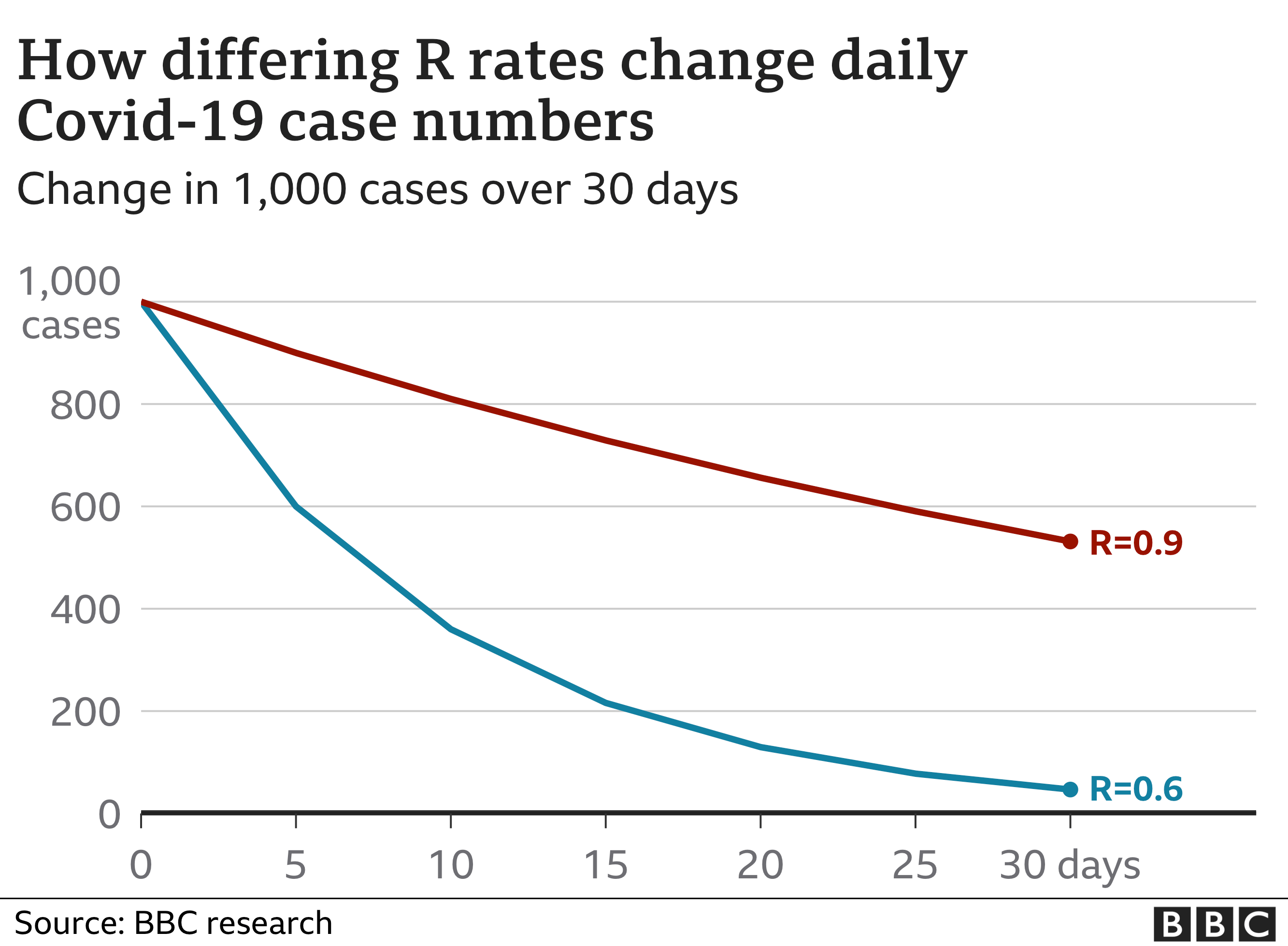

If we consider the R number - the average number of people each infected person passes the virus on to - it was about 3.0 in the run up to the first lockdown and anything above 1.0 means cases are climbing.

R fell to 0.6 during the first lockdown.

Then every 1,000 infected people passed the virus on to 600 others, who passed it on to 360 others and so on.

But if the new variant is 50% more transmissible then the R number, in the same lockdown conditions, would be about 0.9.

Then 1,000 infected people would pass the virus onto 900 others, then 810 and so on.

As you can see this leads to far slower decline.

And that assumes lockdown can get R down to 0.9 in areas where the new variant has become the most common form of the virus.

If, as some studies suggest, the variant is about 70% more transmissible then R may stay above 1.0 and cases may not fall at all.

"We'd at best flatten the curve, keep numbers at a roughly constant level, and that's frankly why there is so much emphasis on getting vaccine into people's arms as quickly as possible," said Prof Ferguson.

It is hard to lockdown even harder as there are some parts of society - hospitals, supermarkets - that need to be kept open.

What happens to the number of cases over the coming weeks will be closely monitored. If this lockdown is less effective then we will have to live with it for longer.

There have been some encouraging signs over the Christmas break, which was a bit like a lockdown due to school holidays and other restrictions.

"We are in a very difficult situation here, but my initial assessment of the last few days is that the rate is slowing which is good news," Prof John Edmunds, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine told the BBC.

He added: "It looks likes those restrictions should be sufficient to stop the increase, whether they will be sufficient to bring cases down sufficiently we are yet to see."

Eventually, the vaccine will give people immunity so we do not need the same controls on our lives.

Now more than ever this is a race between the virus and the vaccine.

Source - BBC World News

THERE are several areas where, during 2020, South African ruling class efforts to reign in the deadly Covid-19 virus will be considered by workers very critically, indeed as outright failures: relief, prevention, treatment and vaccines.

But 2021 need not suffer the same mistakes if basic decency replaces our government’s neoliberal policies, austerity programmes and the Health and Trade Ministries’ fear of offending Western and BRICS-country capitalists and states.

The recent 18 000 infections set new records which demands much bolder actions by government and society as a whole

Relief

First, it became immediately apparent in March 2020 once the Covid-19 lockdown was announced, that the state had little concern for the extreme inequality, unemployment, poverty, gender-based violence and environmental crises that have made the majority’s lives miserable. The feeble R350/month emergency grant and temporary partial top-up of the monthly child, old-age and disability grants were tokenistic, and barely raised consumer buying power, much less helped people thrown deep into poverty.

The state’s administrative system was chaotic, especially in the Department of Labour’s Temporary Employer/Employee Relief Scheme (TERS). Auditor General Tsakani Maluleke discovered “failed coordination, monitoring and relationships across the three spheres of government. Where implementing agents were involved, we found weaknesses in coordination and monitoring, which compromised delivery, transparency and accountability.” As for the South African Social Security Agency’s emergency relief, she criticized “outdated, limited databases and inadequate verification controls.”

Given these problems in 2020, let 2021 be the year that South Africa finally implements a Basic Income Grant. It will be easily paid for with progressive (redistributive) taxation, so as to lower our extreme, worsening income inequality, and also to limit the technological crises, corruption and means-testing bureaucracy in our welfare system. It is long overdue for the streamlining of social welfare so that not only can there be appropriate targeted relief where special circumstances require, but that a universal system of income support be available to end income poverty, cut back our toxic inequality, specifically improve women’s economic status, and boost the economy from below (through raising consumer buying power of people who mainly spend on locally-made items).

It so often feels that government has no time for the ‘precariat’ – the proletariat which does not have a steady job and benefits but instead works hand to mouth, maybe in the ‘informal sector’ or gig economy, typically below the state’s radar. Covid-19 was generally catastrophic for our lower two-thirds of the working class, and StatsSA’s unreliable figures won’t tell you this because the agency’s bean-counters don’t know or care, as they proved by claiming the unemployment rate was reduced from 30 to 23% during lockdown’s worst months.

We now hear from StatsSA that job losses from March-September were not that bad. Only 620 000 non-farming jobs were lost if we compare September 2020 (9.58 million) with March (10.2 million). StatsSA also claims that the numbers of people of our class who simply gave up looking and dropped out of the labour force from March-September rose by 2.3 million.

Even if we take these statistics as reliable, which would be a miracle since the economic carnage is so much worse, this represents a decline from 59.5% labour force participation in March, to just 54.2% in September. The terribly low numbers show once again that South African capitalism is unable to deliver jobs, eradication of poverty and more equal society. (The country’s population is 60 million and 40 million are of working age, so if StatsSA is correct, only 22 million of us have any hope of gainful employment, but the very low number – 9.6 million – of non-farm jobs reveals the obvious limits of the labour market.)

To help the working-class recover and help our youth find their first employment, we heard there would be 800 000 new temporary public sector jobs, with expectations of payment a mere R12/hour (the Expanded Public Works Programme minimum wage). But the first reports from the Presidency on December 1 are desultory: “400 000 opportunities supported, with several programmes in the recruitment or beneficiary identification phase” (revealingly ill-defined), of which 300 000 are in the school system. Yet it is most likely with the rapid spread of the Covid-19 variant, no in-person schooling will be possible and so it is likely that more lost months of education loom ahead for our ill-served students.

Attempts at bridging the digital divide through cheap data are welcome at many of our universities, but it is revealing that the main cellphone and data networks are recording healthy profits for IT capitalists – at the expense of ridiculously high communication costs. Capitalist advances are, as ever, at the expense of the ability of mostly-black South African youths to survive the 4th Industrial Revolution. The slogan “we are in this together” is proven meaningless and hollow in every respect. In 2020, state relief from the Covid-19 educational crisis appeared non-existent when it comes to distance learning, so 2021 must show immediate improvement.

On top of this chaos, Treasury’s extreme budget cuts are devastating. We know they were announced to please the International Monetary Fund in June, in the form of self-imposed ‘conditionality,’ so as to raise an unnecessary, unpopular $4.3 billion IMF loan. Then these were amplified in the October medium-term budget. They are particularly devastating to many government departments and municipalities that the working class desperately depends upon, and also to the trust between the state and its civil service gave the government’s reneging on the 3-year wage deal in the budget last February.

Budget cuts are hitting the delivery of housing, basic services, education and healthcare – all victims of austerity even when Covid-19 appeared on the immediate horizon in February. That month, as the world’s worst pandemic in a century, bore down on South Africa, the ANC government decided the health budget should be chopped by R3.9 billion.

Worse, scam announcements of relief followed in June. The idea that a South Africa facing at least 8% GDP decline for 2020 was benefiting from the government’s ‘R500 billion fiscal stimulus’ was often repeated. Biased and pro-rich journalists and naïve UN agencies regularly report this statistic without critical examination of the components. Our generous estimates, like the Institute for Economic Justice and Business Day columnist Duma Gqubule, are that actual net fiscal stimulus spending in 2020 is below R50 billion.

Moreover, the alleged ‘R500 billion monetary stimulus’ was pathetic: on the one hand, a welcome 3% decline in interest rates, but on the other a failure to use Reserve Bank bond-buying power to boost state spending capacity even though such a strategy was deployed in many other countries including many without our resource base and low inflation rate.

And to make their pro-rich bias yet more explicit, both the Reserve Bank and Treasury further loosened exchange controls. Their officials are still not investigating – much less prosecuting – the 3-7% of the country’s national income that flees as Illicit Financial Flows, or the 35-40% of procurement funding in the form of overcharging on outsourced work by corporations, or systemic corporate crime including tax-dodging schemes and currency manipulation (which in other jurisdictions, such as the U.S., the banks gaming the South African rand pay millions of dollars in fines for).

The most disturbing aspect of the relief we are meant to be getting, as innocent unwitting victims of Covid-19, is the lack of state concern about who is infected and who is dying, according to our class, race and geographical situations. The gender breakdown is available, but why do the different statistics of Covid-19 positive status or death rates go unreported by the state, in the world’s most unequal society? Why do we not know if the infection rate for blacks is higher than whites, or what is the death rate by income, or which specific hot-spot sites should we avoid in townships and shack settlements – as all other countries tell their citizens?

One reason, we suspect, is that the state has truly given up on halting Covid-19’s spread in our high-density zones, our poor areas, our informal markets, our workers’ indoor spaces. Without knowing which parts of our population are suffering most, aside from the health-apartheid public-private financing divide in which half the resources are used by just 14% of the population, then both relief and prevention will be ineffectual, as they clearly have been.

Finally, the security forces’ arrest of 300 000 people (mostly for petty violations) – and murder of a dozen – revealed the opposite of relief: repression. The way the overzealous Police Minister Bheki Cele chortles that the arrested will retain criminal records reveals totalitarian tendencies that require a rapid U-turn.

In short, there was no genuine Covid-19 relief destined for the masses. Our society instead gives relief to those who build high walls and private hospitals: the rich, those who can work from home, those whose children can learn online and who keep free of Covid-19 because of private medical aid schemes and large suburban properties unavailable to the mass of the population.

Prevention

The super-spreader events the government failed to prevent, especially youth parties in the coastal cities early in December, are being blamed for the upsurge of infections, now far worse than at any prior time, even June-July when at the peak, South Africa’s infection level was the world’s fifth highest, behind the U.S., Brazil, India and Russia.

We expected resources to flow into the rapid construction of housing with more space than tiny RDP houses so as to provide a ‘decanting’ option to those stuck in slums. We anticipated the rapid roll-out of water and sanitation systems so each yard is serviced as was promised in 1994. We thought all schools would finally get real toilets, not dangerous pit latrines. We thought that especially in the cold months, the electricity would stay on so we could heat food properly, boil water and keep warm – instead of suffering Eskom’s new ‘load reductions’ targeting poor people and bankrupt dorpies. But more importantly, we expected that the government would use the lockdown to employ more health workers, insource the community healthcare workers improve the infrastructure in our hospital as promised and provide frontline with adequate and safe PPEs.

All of these were reasonable expectations that would have prevented much of the mid-2020 and December 2020 waves from crashing on all of us. Epidemiologists know the ‘social determinants of health’ are vital. But this government has since 1994 been committed to neoliberalism as public policy: the exact opposite of the necessary state role in bolstering social support, ensuring mutual aid, guaranteeing employment, and committing to preventative healthcare.

Typical of the non-prevention attitude is working-class transport. It was in mid-2020 that the kombi taxi industry demanded R4 billion monthly so as to comply with the 70% capacity level that the public health experts recommended. Instead, a tokenistic amount was offered and rejected. The government could easily have found the funding and kept the super-spreading kombis from raising our infection and death rates. But its bias towards austerity and lack of regard for workers led kombis to become death traps. On the other hand, the government allowed destruction of the rail infrastructure to the working-class residential areas while pumping billions to the elitist Gautrain.

What is needed is a sector-by-sector consultation with both workers and other citizens who use service and who can determine where safety and hygiene are risky – and what state support would promote better Covid-19 prevention. The government has, instead, imposed clumsy, illogical, out-of-touch strategies without the nuance we need to balance our economic survival with public health management.

The arrogance of nationalist politicians is an easy explanation for this lack of serious consultation. But another structural problem is how useless the NEDLAC negotiating chamber has been, as we have previously remarked. This is not simply because groups like SAFTU and the C19 People’s Coalition are locked out for the selfish, narrow and conservative reasoning that we will rock the boat. It is also that NEDLAC is genuinely lacking in creativity, vision and courage. We term the main site of consultation on Covid-19 a ‘class snuggle’ – when in this moment of massive suffering it is far more appropriate to defend poor and working-class interests in the class struggle.

Vaccines and treatments, following the 20-year old ARV model of treating AIDS

The new crisis the government has landed itself in is the expectation that South Africa would be part of a multilateral solution similar to the UN Fund for AIDS, TB and Malaria: the infamous Covax. Set aside the debate about whether the government cares so little as to compel the private sector to make our country’s Covax payments.

The real problems here are four-fold:

- Donald Trump’s imperialist Operation Warp Speed is based on highly-subsidised ‘vaccine nationalism’ so as to advance his ‘America First’ ideology (with similar versions in other countries), and given the structure of U.S. capitalism, even the neoliberal Democrat Joe Biden will probably not change this formula for corporate success and Yankee jingoism;

- Intellectual Property rights compel states like South Africa to negotiate in an irrational bilateral manner with all-and-sundry Big Pharmacorps for vaccines that may not be appropriate for South Africa and the rest of the continent (Pfizer-BioNTech with its extreme cold-storage requirements, Moderna, Johnson & Johnson, Janssen, Novavax and others still emerging );

- The Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa bloc stands as a clear failure, both because the Brazilians support the U.S. and Europe in defending Western Big Pharmacorp profiteering, and because the BRICS Vaccine Centre announced during the Sandton Summit in 2018 remains a fairytale so is the call for the state created pharmaceutical company remain a pipe dream under the neoliberal ANC government (just as does the BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement meant to be an alternative to the IMF), and so the Russian Sputnik V and Chinese Sinopharm vaccines are being sent to all corners of the earth but not to BRICS partner South Africa; and

- the only recourse to avoid these traps is the World Health Organisation’s Covax system, even though it has only negotiated to acquire the most inferior (70% effective) Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, and in any case, Covax can only assure a very small share (less than 10%) of the doses South Africa will need to ensure the effective universal rollout of the vaccine, and then only after April.

These four pre-existing conditions of medicine-capitalism mean that a Covid-19 ‘vaccine apartheid’ is now festering. The imperialist character of the global health system is reminiscent of the late 1990s and early 2000s when if you had R100 000 for a year’s supply of ARV medicines to treat AIDS, you could live – i.e., mostly the small number of white South African men who could afford the insane mark up by Big Pharma.

But something changed when the Treatment Action Campaign and its allies – including most of us in the leading trade unions – fought medical apartheid, putting enough pressure on both our AIDS-denialist government and the World Trade Organisation and other multilateral agencies, to reject Big Pharma’s power. By 2001, an exemption was confirmed at the WTO, which meant we could import generic ARVs or make them in our own factories (including Aspen’s) through ‘compulsory licensing.’

That victory meant the cost structure changed radically, and after Thabo Mbeki’s AIDS denialism was defeated in 2004, our success as healthcare activists soon allowed eight million people living with HIV to get free ARV medicines through our public health system. The result was a rise in life expectancy from 52 in 2005 when rollout began, to 65 today.

By reminding ourselves of our history of fighting Big Pharma capitalism and WTO Intellectual Property imperialism, there now appears a much different route than the three-way cul de sac.

Our aim, identical to all other people in the world, is to acquire both Covid-19 vaccines and good quality, reliable treatment. The route we suggest, completely ignored by President Ramaphosa in his speech this week, is actually being followed by South Africa’s representative to the World Trade Organisation, Mustaqeem Da Gama. He and Indian counterparts deserve all credit for pursuing an end to Intellectual Property on pandemic vaccines, so as to assure worldwide manufacture and distribution of many billions of doses of generic Covid-19 vaccines and treatments.

We know that the imperialist countries are blocking Da Gama’s efforts, and last month delayed a critical vote to exempt Covid-19 medicines from corporate profiteering. But we also know that a similar situation existed twenty years ago when, likewise, the Western powers were unsympathetic to generic AIDS medicine supply – until in September 2001 the U.S. experienced not only airplanes crashing into the World Trade Centre and Pentagon, but also anthrax circulating in envelopes, sent by domestic terrorists. As a result, the U.S. urgently needed millions of doses of the Cipro antibiotic antidote, and forced the drug’s manufacturer, Bayer, to lower prices and allow generic medicines. With that precedent, it was then unable to defend its hypocritical stance enforcing Intellectual Property on (publicly-subsidised) AIDS medicines two months later at the WTO summit in Doha.

SAFTU demands

In the same spirit that we addressed our AIDS pandemic with generic medicines and public-sector provision, we insist that these demands be met:

- For identifying where relief is due, it is essential that the state’s hidden data on the race, class and geographical incidence of both Covid-19 positive South Africans, and those suffering hospitalisation and death, be made available – just as any civilised public health service is doing anywhere. This is especially true since South Africa is the world’s most unequal country by income and suffers such strong residues of racial discrimination. To continue to aggregate the poor townships with the wealthy suburbs within data provided to the public is an insult to our intelligence, and a barrier to identifying how relief should be targeted and distributed, especially now that the health service needs urgent bolstering.

- Expanded state relief payments and a genuine stimulus, e.g., through ending austerity and urgently implementing a Basic Income Grant (as noted above). Rapid resumption of relief payments is especially important for workers (e.g., in the hospitality industry) whose unscrupulous employers have no intention of paying them for December-January now that we are back at Level 3, through no fault of their own. Since the TERS system was so mismanaged, with April-September reruns of missed payments only being resolved by the Unemployment Insurance Fund in December, the government should rethink its extreme stinginess, and ensure all social welfare and emergency Covid-19 payments are resumed and raised to more appropriate levels. The SA Reserve Bank is fully capable of handling emergency state bond purchases to fund this, as it showed in March-April albeit at a tiny fraction of what many in society called for, in terms of Quantitative Easing – especially since the threat of inflation is non-existent in our depressionary economy.

- In terms of prevention, workers are frightened because we are now at much higher risk of infection by the Covid-19 variant, as it spreads rapidly from hot spots across the country, back to cities as workers return home from holidays. Some high-risk sites such as kombi taxis should finally be given subsidisation to reduce carrying capacity to safe levels. Employers’ safety precautions need urgent revisiting, with not only rapidly stepped-up Labour Department inspections but antigen testing for all workers returning to their jobs in coming days. The government’s promised efforts to test, trace, track and if need be isolate those who have contracted Covid-19 were never taken seriously by government or employers, but now that the second wave is worse than the first, they should be.

- When it comes to access for Covid-19 vaccines and medicines, South Africa’s government should remember lessons from the AIDS pandemic. For example, Big Pharma and governments which have placed copyrights on Covid-19 vaccines and treatment must publish (open-source) all details about the medicines’ components and also waive any patents, so we can learn whether generic production systems in places as diverse as India, Cuba and South Africa can quickly produce at scale. The South African government should take real leadership here, given our experience as the country with the most people living with HIV who use generic ARVs.

- Vaccine nationalism must fall! We must impress upon Joe Biden and European leaders that the Trump narcissism witnessed so explicitly in vaccine apartheid is immoral and simply will not be tolerated, as we repeat 2001’s accomplishment, namely ensuring life-saving medicines during pandemics become part of a global commons.

- Also with regard to medicine access, our own internal health apartheid must be ended, through a National Health Insurance which will not simply give class-based vaccine access to the top 14% per cent of South Africans – those now on private medical aids (especially Discovery, which is bragging about exclusive vaccine provision to its members) – but that will cross-subsidise so a rational roll-out of the vaccine to everyone needing it can be accomplished, starting with our brave healthcare workers.

- Likewise, the same principles apply to the treatment drugs now being tested, although many have not yet proven universally effective and safe (the names include remdesivir, lopinavir-itonavir, interferon beta, corticosteroids, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, dexamethasone and ivermectin; and Regeneron’s monoclonal antibody therapy is still extremely scarce, being the drug apparently used to successfully treat the Covid-positive imperialist leaders Donald Trump, Rudi Giuliani and a few other Trump cronies in the United States).

- While neither Western nor South African Health Products Regulatory Authority officials yet fully approve most drugs as effective Covid-19 treatments, and while new medicines will hopefully be tested rigorously so quack cures are quickly eliminated, it is obvious that we need urgent access to much more urgent medical infrastructure including Intensive Care Units, hospital beds and oxygen, as well as Personal Protective Equipment for health workers, and so anyone standing in the way – such as the austerity-minded government or private hospitals and clinics unwilling to share resources for the good of the entire society – should be replaced or nationalised forthwith.

- Finally, what’s good for South Africa must also necessarily apply to the entire African continent and all the poorest countries, so instead of locating our government as a middle-income country – and one which permits relatively easy access via our airports to the rest of our sisters and brothers across a continent whose borders were, after all, drawn by a few European colonial powers in 1885 – it is vital that we act as a unified body. Having our President currently serving as the African Union chairperson is potentially a benefit – but the mixed messages he has sent on debt cancellation for poor countries already signals a degree of unreliability. If, because of our failure to ensure all Africans get vaccines and treatments in an urgent and equitable way, South Africa is once again considered the ‘Yankees of Africa’, this will be yet one more unacceptable sign of our neocolonial, sub imperial location in world capitalism.

These are demands that SAFTU takes into 2021, but it is the working-class and our allies who will ensure that they are not empty words, but the beginning of a Pan African strategy to ensure all our peoples have the healthcare – and relief plus preventative measures – that we deserve!

In this context, we must urge the working class to take their destiny into their own hands. The state has abandoned them. We need to demand vaccinations from our workplaces. No miner should go underground without being inoculated against C19, no teacher should teach without being inoculated, no health worker should have to put their life at danger because our government is too stingy to procure the vaccines. A mass working-class campaign for the procurement, distribution and administration of the vaccine is necessary. Every workplace, every township and community should be a site of struggle for the vaccine.

And if these sorts of reasonable demands continue to be ignored, we can confidently predict that the society will judge the ruling party harshly at the ballot box or through rising electoral apathy, in this year’s municipal voting, as well as in the streets as South Africa’s spirit of civil society protest never fades.

- Zwelinzima Vavi is secretary-general of the South African Federation of Trade Unions.

Source - The African Mirror

BRITAIN has become the first country in the world to approve a coronavirus vaccine developed by Oxford University and AstraZeneca as it battles a major winter surge driven by a new, highly contagious variant of the virus.

Britain has already ordered 100 million doses of the vaccine, and the government said it had accepted the recommendation from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) to grant emergency authorisation.

The approval is a vindication for a shot seen as essential for mass immunisations in the developing world as well as in Britain.

In December, Britain began rolling out the COVID-19 vaccine developed by Pfizer and BioNTech, the first Western country to start vaccinating its general population in what was hailed as a decisive watershed in defeating the coronavirus.

But wealthier countries have the capacity to roll out vaccine programmes more swiftly than poorer nations.

And some high-income countries have bought enough doses in advance to vaccinate their populations several times over, leaving fewer doses for low- and middle-income countries said Duke University researchers.

We examine the front-running vaccines and ask experts if efforts to get them to the 22% of the world’s population – or 1.3 billion people – living in developing countries will succeed.

What is the main obstacle to these vaccines reaching developing countries?

Anna Marriott, Health Policy Manager, Oxfam – “The number one challenge we’re seeing is the unprecedented scale of supply that is needed. So actually producing enough of the vaccine is one of the biggest constraints.

“It’s very clear that unless the companies relinquish their control (on intellectual property)… and enable more producers to produce the vaccine, we are definitely not going to get to the supply that we need, as quickly as we need it.”

Andrea D. Taylor, Assistant Director of Programs, Duke Global Health Institute – “We need to focus on timing and equity of distribution.

“For the best outcomes globally, we need poor and rich countries to receive doses at roughly the same time.

“However… it looks like high-income countries are likely to be well-covered by the first half of 2021 but low-income countries will still be waiting. Vaccine hesitancy is an increasing issue. Misinformation about the pandemic and the potential vaccines is breeding mistrust. This is an issue in all countries… and may prevent people from taking the vaccine.”

Roz Scourse, Policy Advisor, Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) – “Vaccine nationalism is a huge challenge for access to low and middle-income countries.

“Even if people in high income countries get access, if COVID is still circulating in other populations around the world we’re not going to see an end to the pandemic.”

Where do you rank the 3 vaccines on these issues? Which one could reach the poorest soonest?

Taylor, Duke Global Health Institute – “In terms of efficient distribution in poorer countries, the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine appears to be the winner so far. It is stable at standard refrigerator temperatures.”

Scourse, MSF – “For Pfitzer and Moderna, there are a few different prices out there but basically, very high prices per dose which will definitely restrict their access to low and middle-income countries.”

Marriott, Oxfam – “I would rank AstraZeneca and Oxford first in terms of the actual price that they’re selling this vaccine for.

“AstraZeneca and Oxford have clearly done more to expand production by licensing their vaccine to more manufacturers in the global south.

“On logistics, Pfizer and BioNTech needs ultra-cold chain which makes it much more tricky. But it’s not impossible.

How can these vaccines be made more accessible?

Marriott, Oxfam – “What we want to see AstraZeneca and Oxford do now is to commit to an open licence so more vaccine manufacturers can get on board. We think really the power is in their hands to end this epidemic by the end of 2021.”

Scourse, MSF- “Both price and supply challenges can be overcome if we look at more systemic issues in intellectual property.

“We need to open up intellectual property, including patents, so any manufacturer around the world could produce successful products without fearing barriers.”

Source – Thomson Reuters Foundation

AFRICA’S 1.3 billion people may have fared better than expected in terms of containing COVID-19 but the pandemic has dealt a severe blow to already weak health services, raising fears of excess deaths from other illnesses plaguing the continent.

A World Health Organization (WHO) analysis of 14 African countries found a more than 50% decline in services ranging from the provision of skilled birth attendants to the treatment of malaria cases in May, June and July this year.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has brought hidden, dangerous knock-on effects for health in Africa,” Matshidiso Moeti, WHO Regional Director for Africa, said in a recent statement.

“With health resources focused heavily on COVID-19, as well as fear and restrictions on people’s daily lives, vulnerable populations face a rising risk of falling through the cracks.”

Africa has recorded more than 2.4 million cases of COVID-19 and more than 57,000 deaths, according to the African Union’s Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, with the lower percentage of deaths due to early and strict lockdown measures.

Here is a look at three of the top killers in Africa and the estimated number of excess deaths caused due to the pandemic in 2020:

1.MALARIA

Each year more than 400,000 people globally die of malaria – a preventable and treatable mosquito-borne disease. An estimated two-thirds of deaths are among children under the age of five.

Sub-Saharan Africa shoulders the heaviest burden, accounting for 94% of malaria deaths worldwide. Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, Niger, Mozambique and Burkina Faso accounted for up to half of world’s malaria deaths in 2019.

Due to the pandemic, many malaria prevention campaigns – which include key distribution of bed-nets – have been delayed and patients unable to get to clinics for treatment due to fear of visiting a clinic or lockdown restrictions.

The WHO projects such disruptions will result in more deaths due to malaria than COVID-19 in sub-Saharan Africa in 2020.

“It’s likely that excess malaria mortality is larger than direct COVID-19 mortality,” said Pedro Alonso, director of WHO’s malaria programme on World Malaria Day last month.

The WHO forecasts a 10% disruption in access to anti-malarial treatment could lead to 19, 000 additional deaths in Africa this year and disruptions of 25% or 50% could result in an additional 46,000 or 100,000 deaths respectively.

2.TUBERCULOSIS

Tuberculosis killed 1.4 million people globally last year and is one of the top 10 causes of death worldwide.

More than 95% of TB deaths are in developing countries with South-East Asia accounting for 44% of deaths, followed by sub-Saharan Africa with 25%.

These include countries such as South Africa, Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Tanzania, Mozambique, Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda and Zimbabwe.

Due to the pandemic, in many countries doctors and health workers have been shifted from tracking TB cases to tracing people infected with COVID-19 and equipment and budgets reassigned in the fight against the pandemic.

As a result, millions of TB diagnoses have been missed.

Modelling by the WHO suggests this is likely to result in 200,000 to 400,000 excess deaths from the disease this year alone.

3.HIV/AIDS

More than 38 million people worldwide are currently infected with HIV with almost 26 million living in African nations, including Zimbabwe, South Africa, Botswana and Mozambique.

From the 690,000 people who died from HIV-related causes in 2019, more than 60% were in sub-Saharan Africa. Women and girls accounted for about 48% of all new HIV infections globally last year – in Africa, they accounted for 59%, according to UNAIDS.

The pandemic has led to people having their treatment interrupted because HIV services are closed or because services were overwhelmed due to competing needs for COVID-19.

Modelling conducted by UNAIDS and the WHO found that a six-month disruption of antiretroviral therapy could lead to more than 500,000 extra deaths from AIDS-related illnesses in sub-Saharan Africa.

This would take AIDS-related deaths in the region back to 2008 levels when almost one million people died, said UNAIDS.

Source – Thomson Reuters Foundation