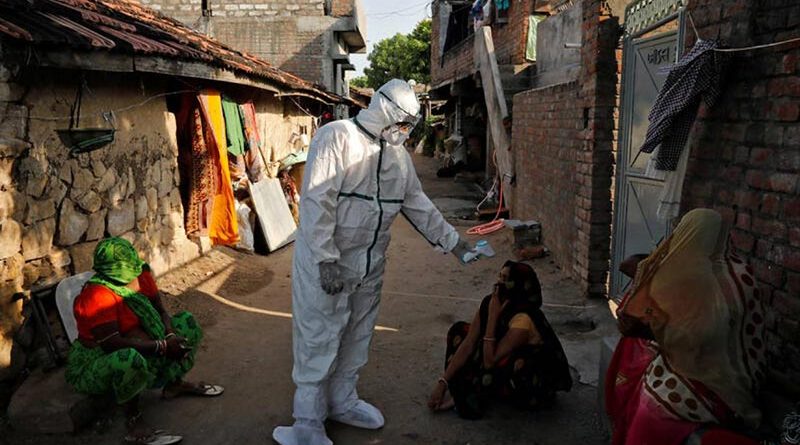

THE COVID-19 pandemic has strained health systems and disrupted essential health services in Africa. Countries are working to restore and strengthen key services to better withstand shocks and ensure quality care. Regina Kamoga, the Executive Director of Uganda’s Community Health and Information Network and Chairperson of the Uganda Alliance of Patients Organizations, speaks about the impact of COVID-19 and solutions to restore essential health services.

What is the impact of COVID-19 on patients seeking services for other diseases?

Many governments in Africa took measures to combat the spread of COVID-19. However, some of the measures totally disrupted the supply chain and health care service delivery system as all efforts were focused on COVID-19. Governments diverted personnel and resources away from priority diseases. Patients with HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, cancer, hypertension, hepatitis B, epilepsy, sickle cell, as well as mental health, maternal or childhood conditions, faced an increased risk of complications and death due to inability to access healthcare because of transport restrictions, curfew, and fear of contracting the virus from healthcare settings. The situation was made worse by existing healthcare system challenges which include among others inadequate human resources, financial, infrastructural, supply chain and logistical challenges.

Access to medication has been a major problem for patients with chronic conditions who rely on drugs for their survival and improved quality of life, as they were unable to get their refills while others could not afford medication due to lack of income. On the other hand, self-purchasing and stockpiling of antibiotics and other medicines for those who could afford presented another challenge of medication safety including antimicrobial resistance.

In Uganda patients who had been newly diagnosed with cancer were not able to be initiated into treatment while others missed their three-month refills for hormonal treatment. These delayed initiations and interruption of treatment cycles resulted in increased stress, anxiety, disease progression, recurrence and premature death.

What are the solutions?

Initially, the top-down approach worked very well where top leadership was a key factor in mitigating the impact of the COVID-19. This led to governments instituting lockdowns and other preventive measures including social distancing, national, regional and local lockdowns, quarantines, wearing of masks and handwashing. The lessons learnt have shown that the lack of community engagement and patient involvement right from an early stage in the COVID-19 response was a big oversight. Community systems must be urgently strengthened.

Empowering patients to self-manage chronic conditions, especially during such unusual times where they cannot access medical centres as often as possible, is necessary while emphasizing health literacy and telemedicine.

Efforts by key stakeholders to address the psychological needs of the population to mitigate the impact of mental health issues resulting from the challenges of this epidemic is required and should be integrated in all aspects of the response.

It is important to prioritize health care by increasing health sector budgets and reducing reliance on foreign funding. Governments also need to fast track universal health coverage through national health insurance schemes to ensure that vulnerable people access safe and quality health care.

What is the importance of the community, particularly as we face complacency and a possible resurgence in cases?

The potential of community involvement in the COVID-19 response has not been fully exploited. Strengthening community structures such as the role of community leaders, including political, religious, cultural leaders as well as community extension health workers in mobilizing and engaging community members to effectively respond to COVID-19 is invaluable.

In Uganda, community health workers are usually the first point of contact in the community and source of health information. They are trusted, well connected and use appropriate community engagement approaches to mobilize and sensitize the community. They are best placed to demystify the myths and perceptions relating to COVID-19 in the community and address complacency. Involving them in community-based surveillance, case management, contact tracing is a winner.

The Ministry of Health has developed a national community engagement strategy. It is aimed at strengthening existing community health systems for integrated people-centred primary health care. Its success will depend on translating theory into action and commitment of all stakeholders.

Source – WHO-African Region.

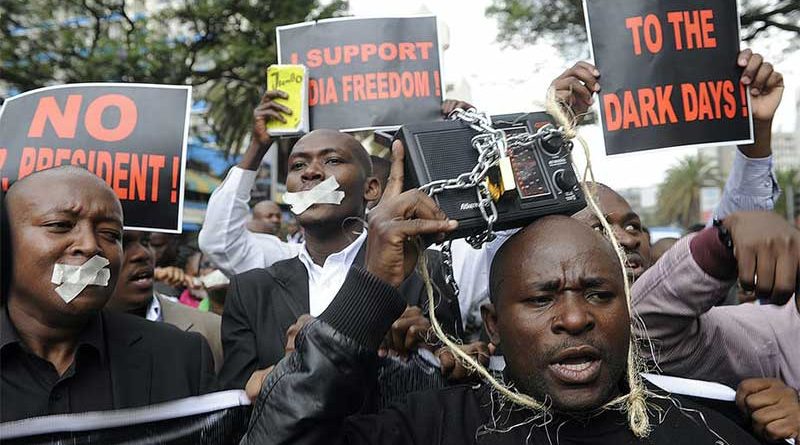

ALMOST a decade after the United Nations set aside November 2 as a day to reflect on ending impunity for crimes against journalists, crimes against media workers in Kenya are still widespread. The coverage of elections and corruption cases has typically prompted these attacks. But now the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed more of the state’s intolerance towards journalists in their line of duty.

Kenya confirmed its first case of COVID-19 in mid-March 2020. By the end of the month, the government had imposed a curfew to stem infections. Soon afterwards, images of police officers using excessive force to enforce the curfew surfaced in the media. Three deaths were reported as a result of police brutality.

The police then began harassing journalists who reported on their brutality. By October 2020, there had been at least 48 reports of violations against journalists reporting on the pandemic. Twenty two of those cases occurred within six weeks of the first case of COVID-19. The violations have included physical assault, arrests, verbal threats and online harassment.

Although journalists were listed as essential service workers and exempted from curfew restrictions, reports indicate that on-duty journalists were harassed.

At least 10 journalists and digital content creators have been arrested or threatened with prosecution under the Computer Misuse and Cyber Crime Act 2018. They were accused of publishing and spreading false and alarming information on social media about the new coronavirus. At least 10 others were arrested under the Public Order Act, for allegedly flouting the curfew.

Some commentators have categorised these recent incidents as politically motivated – attempts to camouflage the government’s inefficient handling of the coronavirus crisis. Kenya’s ministry of health has been accused of corruption and ineptness in its COVID-19 response, which it has refuted.

Read more: New media voices are telling Kenya’s COVID-19 stories — from the ground up

Impunity

The police have not effectively investigated threats and attacks against journalists. There is no evidence to suggest that any police officer has been prosecuted for attacks or threats against journalists since the pandemic began.

It is no wonder then that Kenya has dropped three places and is currently ranked at 103 out of 180 countries on the 2020 World Press Freedom Index. This can only be remedied by the media continuing to highlight crimes against journalists to ensure that justice is served.

But journalists don’t necessarily get support even from the media houses that employ them. Some employers have used the COVID-19 pandemic as a pretext to enforce staff layoffs and salary cuts. According to the Kenya Editors Guild, more than 300 journalists have lost their jobs in the past nine months. Some of them were notified via text message.

This is made possible by the wider culture of impunity, unfavourable laws, and media ownership that is tied to the ruling elite.

Shifting media goal posts

Kenya has a long history of using repressive laws to silence and punish journalists for doing their jobs. At independence, the role of the media was to address the challenges of poverty, disease and ignorance. Many African governments, including Kenya, nationalised media and exercised unfettered control over them to promote their development agendas.

Gradually, the media were transformed into a propaganda department for Kenya’s one-party state. Draconian laws were passed to curtail press freedom and other forms of public agitation. Consequently, the history of the Kenyan media in the 1970s and the 1980s is filled with episodes of state interference, harassment and torture of journalists.

The re-introduction of multiparty politics in 1991 expanded the ownership base of the media. Journalists grew bolder. But as former president Daniel arap Moi struggled to maintain his grip on power, the 1990s saw renewed attempts to curtail media freedom. The passage of the 2010 constitution came as a relief because it expressly articulated media freedom.

Yet journalists and media outlets in Kenya faced increased pressure after Uhuru Kenyatta assumed office in 2013. The Jubilee Party’s contempt for the media was evidenced when the president stated that newspapers were only good for “wrapping meat”. The current administration has continued to enact laws that undermine media freedom. Some of these laws are the Media Act, 2013, Kenya Information, Communication (Amendment) Act, 2013 and Security Laws (Amendment) Act, 2014.

These laws imposed tough penalties on journalists and expanded offences for which they could be punished. The government’s increased intolerance of the media culminated in the temporary shutdown of four independent TV stations after they covered former opposition chief Raila Odinga’s symbolic presidential inauguration in 2017.

Media freedom and democracy

The Kenyan government is a signatory to treaties like the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Signatories are required to protect media workers from threats by state and non-state agents.

There is an intrinsic link between media freedom and democracy. Vibrant, independent media are crucial for Kenya to survive as a democratic state. Upholding free expression and media rights – guaranteed by Kenya’s constitution and international human rights law – should be the duty of the government.

Kenya needs to directly address the attitudes that foster the culture of impunity among state agents and the political class. It’s also essential to enforce laws equitably and support journalists who are victims of crime.

Source: The Conversation

COVID-19 cases are accelerating in some parts of Africa and governments should step up preparations for a second wave, the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention said on Thursday.

Over the past four weeks, cases have increased by 45% per week on average in Kenya, by 19% in the Democratic Republic of Congo and by 8% in Egypt, the African Union-run organisation’s head John Nkengasong said.

“The time to prepare for a second wave is truly now,” he said, urging governments “not to get into prevention fatigue mode.”

The continent of 1.3 billion people has so far managed better than widely expected in terms of containing the epidemic, with a lower percentage of deaths than other regions, partly due to strict lockdown measures imposed in March.

There have been 41,776 deaths among the 1.74 million people reported infected with the virus, according to a Reuters tally based on official data as of Thursday morning.

Beginning in August, many governments eased restrictions, however, and a trend of decreasing cases has flattened, Matshidiso Moeti, Africa director for the WHO said in an online press conference on Thursday.

In Kenya, the government allowed bars to reopen on September 28 and cut the nightly curfew by two hours. Schools partially reopened on October 12.

Some easing was justified to help economies in the region to start recovering, Moeti said.

However, “we will need to be dealing with some of these upticks. What is important is to contain them.”

Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta on Wednesday announced a November 4 summit to review the surge in infections, and urged Kenyans to wear face masks properly and practice social distancing to avoid “losing hard-fought-for ground” in the fight against the disease. – Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Source: The African Mirror

OVER 6000 South African government workers illegally got paid R41-million from a special relief fund set up to assist private-sector employees whose salaries were reduced because of the onset of COVID-19.

The payments, made through the Temporary Employment Relief Scheme (TERS), to the civil servants are now the subject of a probe by the Special Investigation Unit (SIU).

Advocate Andy Mothibi, head of the SIU, revealed the irregular payments when he briefed Parliament’s Standing Committee on Public Finances on investigations into the payments made out of the TERS, which is managed by the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF).

The SIU investigation follows earlier work done by the Auditor-General office, which revealed the violations.

Mothibi said the SIU was probing 3959 into which the R41-million was paid. He said the SIU found that of the 3959 accounts, 581 were associated with 3079 beneficiaries. The SIU also discovered that over R300 000 was paid to government officials with no bank accounts.

Mothibi also reported on the good progress made by the SIU. He said a total of 70 criminal cases, involving R1.4-billion, were registered with the South African Police and were currently under investigation by the Special Commercial Crimes Unit.

No arrests have been made in relation to these matters.

Mothibi said the SIU was working together with other law enforcement agencies at the Fusion Center, a special coordination vehicle established by the South African government to crack down on COVID-19 fraud and corruption.

The SIU head also disclosed that the SIU was probing payments made to:

- 59 members of the South African Defence Force.

- Seven prisoners who received a total of R40 657.93

- Seven deceased individuals, with multiple bank accounts.

The SIU also found that the UIF spent R6.1-million on five service providers hired to provide awareness for the TERS special fund, without following supply chain management processes and in violation of the Public Finance Management Act.

Mothibi said the SIU found that the five service providers were required to conduct advertising campaigns in order to create awareness about the UIF Covid-19 TERS, for the duration of 45 seconds, three spots per day, for four weeks on their respective radio channels and related television channels.

He said the UIF’s Bid Adjudication Committee Requested for a deviation from the normal procurement processes in order to appoint the service providers. All the service providers were appointed on a deviation.

“The SIU is conducting a full-scale investigation in order to confirm and or refute corruption, maladministration allegations, and or to determine if there were any undue benefits or gratifications paid to the UIF officials to influence the supply chain management process,” he added.

Source: The African Mirror