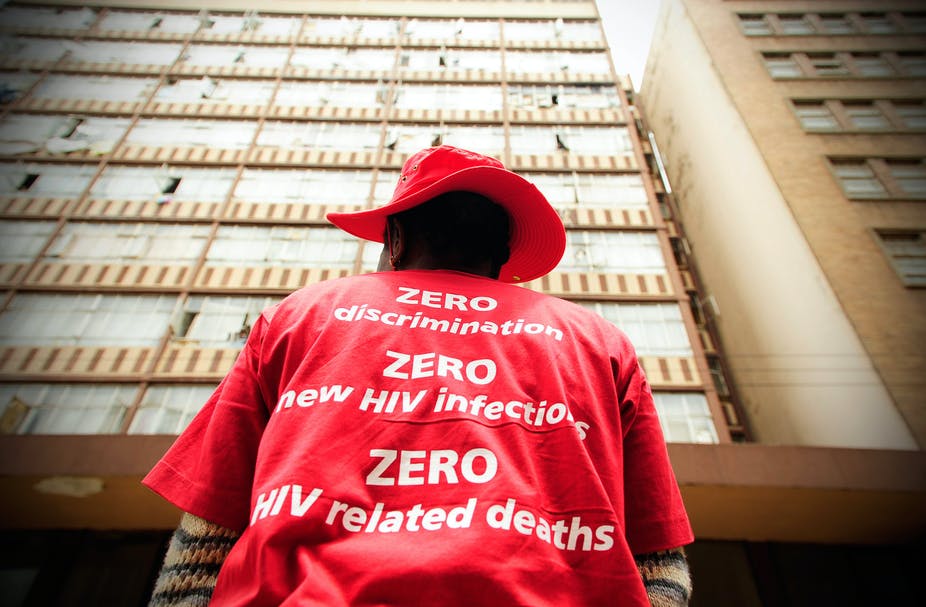

Since 2013, global efforts have been made to gain control over the AIDS epidemic by 2020 through UNAIDS’ 90-90-90 targets. The focus has been to have 90% of all people living with HIV know their status; and of those, 90% initiated on antiretroviral therapy (ART); and of those, 90% reaching viral suppression through ART adherence. Viral suppression means that virus in their blood is undetectable and they cannot transmit HIV sexually.

Much ground has been made towards achieving these goals. To date, 14 countries have reached the 90-90-90 targets. However, missed targets in other countries have allowed 3.5 million HIV infections and 820,000 AIDS-related deaths to occur since 2015.

One of the countries missing the mark is South Africa, which carries 20% of the global HIV burden. By 2018, encouragingly 90% of all people with HIV in South Africa knew their status. However, only 68% who knew their status were on ART; and of those, 87% were virally suppressed. This equated to 61% of all people with HIV in South Africa initiated on sustained ART and 53% of all people with HIV virally suppressed.

Then, by late 2019, COVID-19 emerged and has now swept the globe. This new pandemic has shifted the projected course of public health resources and existing HIV campaigns. The South African National AIDS Council worries that the progress of multi-year strategic plans has been upended. This is a shared concern for many countries with a high burden of HIV.

Get news that’s free, independent and based on evidence.

COVID-19 has put a strain on the country’s already stretched health system. The measures taken to curb the spread have made it hard for people to access routine healthcare and medication for chronic non-communicable disease as well as HIV. Strategies are needed to optimise health-related outcomes for all conditions, while still allowing the healthcare system to combat the novel pandemic.

COVID-19 and health systems

Hard national lockdowns around the globe, including South Africa’s, were essential to slow the transmission of COVID-19 and allow healthcare systems to prepare for the impending wave of critically ill patients.

Unfortunately, these unprecedented country-wide shutdowns have had downstream effects on other aspects of the public healthcare systems. They’ve created a serious threat for countries with a high prevalence of HIV. People relying on HIV prevention, care and treatment services have become even more vulnerable.

People with HIV need ART to survive because there’s no cure or vaccine. During the lockdown, patients were afraid to leave their homes to collect medications. The trepidation was brought on by the fear of contracting COVID-19, but also the threat of police brutality or incarceration through reinforcement of quarantine. For patients who did make it to ART dispensaries, many facilities experienced – and are still experiencing – supply-chain management deficiencies causing medication stock-outs. Additionally, due to the influx of COVID-19 patients, other services (such as reproductive health services) may have been unavailable.

The World Health Organisation and UNAIDS projected that a complete HIV treatment interruption of six months could lead to an excess of more than 500,000 AIDS-related deaths in sub-Saharan Africa over the next year. This is a major step backwards. In 2018, 470,000 AIDS-related deaths were reported in the region.

South Africa has one of the highest numbers of HIV cases and people on ART. The country would experience the largest changes in both HIV incidence and mortality due to ART interruptions. Treatment interruptions or delays will further compromise the immune systems of people with HIV. This could mean disease progresses to where the CD4 count is too low to be reconstituted or opportunistic infections become unmanageable.

These projections should scare everyone. As it stands, since April 2020, 36 countries containing 45% of the global ART patient population have reported disruptions in ART provision. Twenty-four countries are combating stock-outs of first-line treatment regimens. Other by-products of a disrupted healthcare system are that 38 countries reported a substantial decrease in uptake of HIV testing.

South Africa is already seeing a nearly 20% decrease in ART collection in key provinces and a 10% decrease in viral load testing of ART patients since the introduction of lockdown in March. Even shorter, sporadic treatment disruptions can yield additional complications. These include an increase in the spread of HIV drug resistance, which carries long-term consequences for future treatment success.

HIV and COVID-19

Globally, scientists have focused mostly on the increased risk of COVID-19-related illness and death associated with noncommunicable diseases such as hypertension and diabetes.

Sadly, the role other infectious diseases play in health-related outcomes is largely forgotten. Hits to established HIV programmes make people with HIV even more vulnerable to adverse health events. It is, therefore, also important to understand that this same population is at increased risk of COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality.

There’s an intersect between non-communicable diseases and infectious disease, with HIV at the centre. The nature of the virus and the treatment required means that people with HIV are at increased risk of inflammation and metabolic syndrome disease. This puts them at risk of chronic non-communicable diseases – a risk-factor for COVID-19. Furthermore, ART has allowed people with HIV to live longer and naturally develop these comorbidities through increased age. People with active tuberculosis (TB) are over 2.5 times more likely to die from COVID-19. In South Africa, the TB/HIV co-infection rate is above 60%.

The first study published on the effect of COVID-19 infection among people with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa was reported from the Western Cape, South Africa. People with HIV have a 2.75 times greater risk of dying from COVID-19 than those without HIV. Viral suppression did not seem to affect health outcomes, with HIV accounting for about 8% of all COVID-related deaths. There is increased cause for concern when considering the high levels of HIV comorbidity with noncommunicable diseases and TB.

Way forward

The projected models must be taken seriously and strategies are required to sustain all vital health services.

There is an urgent need for global and local differentiated service delivery to ensure HIV service continuity – most critically uninterrupted ART supply – during the COVID-19 pandemic. These strategies could include a change in where HIV testing is provided and treatment is dispensed. Patients could be given longer treatment refills or bulk packs of treatment.

Community-based services could serve both pandemics. Such a strategy could relieve pressure on public healthcare facilities while protecting the most vulnerable populations who need to stay at home to minimise their risk of exposure.

With restricted global movement comes restricted imports of HIV tests and treatments. Countries must include locally manufactured medications within their national ART regimens. Governments, suppliers and donors need to avoid excess HIV-related deaths by creating an uninterrupted supply of ART.

If the world is single-minded and focuses purely on combating one pandemic (COVID-19), forgetting others, the effects of other morbidity and mortality on healthcare systems will be seen for a long time to come.

Source - The Conversation

PFIZER Inc with partner BioNTech SE and Moderna Inc have released trial data showing their COVID-19 vaccines to be about 95% effective at preventing the illness, while AstraZeneca Plc this week said its vaccine could be up to 90% effective.

If regulators approve any of the vaccines in coming weeks, the companies have said distribution could begin almost immediately with governments around the world to decide who gets them and in what order. The following is an outline of the process:

WHEN WILL COMPANIES ROLL OUT A VACCINE?

Pfizer, Moderna and AstraZeneca have already started manufacturing their vaccines. This year, Pfizer said it will have enough to inoculate 25 million people, Moderna will have enough for 10 million people and AstraZeneca will have enough for more than 100 million people.

The U.S. Department of Defense and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) will manage distribution in the United States, likely starting in mid-December with an initial release of 6.4 million doses nationwide.

UK health authorities plan to roll out an approved vaccine as quickly as possible, also expected in December.

In the European Union, it is up to each country in the 27-member bloc to start distributing vaccines to their populations.

WHO WOULD GET AN APPROVED VACCINE AND WHEN IN THE UNITED STATES?

Upon authorization from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the CDC has said first in line for vaccinations would be about 21 million healthcare workers and 3 million residents in long-term care facilities.

Essential workers, a group of 87 million people who do crucial work in jobs that cannot be done from home, are the likely next group. This includes firefighters, police, school employees, transportation workers, food and agriculture workers and food service employees.

Around 100 million adults with high-risk medical conditions and 53 million adults over the age of 65, also considered at higher risk of severe disease, are the next priority.

U.S. public health officials said vaccines will be generally available to most Americans in pharmacies, clinics and doctors offices starting in April so that anyone who wants a shot can have one by the end of June.

It is unclear when a vaccine will be available for children. Pfizer and BioNTech have started testing their vaccine in volunteers as young as 12.

WHEN WILL A VACCINE BE AVAILABLE IN OTHER COUNTRIES?

The European Union, the United Kingdom, Japan, Canada and Australia are all running rapid vaccine regulatory processes.

Many of AstraZeneca’s doses this year are expected to go to the United Kingdom, where health officials have said that if approved they could begin vaccinating people in December. At the top of their list is people living and working in care homes.

In Europe, the E.U. drugs regulator has said it could rule on the safety of a COVID-19 vaccine in December.

Most countries have said the first vaccines will go to the elderly and vulnerable and frontline workers like doctors.

Countries say they are buying vaccines via the European Commission’s joint procurement scheme, which has deals for six different vaccines and nearly 2 billion doses.

Delivery timelines vary and most countries are still drawing up plans for distributing and administering shots.

Italy expects to receive the first deliveries of the Pfizer-BioNTech shot and AstraZeneca’s shot early next year. Spain plans to give vaccines in January.

In Bulgaria, the country’s chief health inspector expects the first shipments in March-April. Hungary’s foreign minister said doses will land in the spring at the earliest.

Germany, home to BioNTech, expects to roll out shots in early 2021 with mass vaccination centres in exhibition halls, airport terminals and concert venues. It will also use mobile teams for care homes. Front-line healthcare workers and people at risk for serious COVID-19 are expected to get inoculated first.

WHEN WILL DEVELOPING COUNTRIES HAVE ACCESS TO VACCINES?

COVAX, a program led by the World Health Organization and the GAVI vaccine group to pool funds from wealthier countries and nonprofits to buy and distribute vaccines to dozens of poorer countries, has raised $2 billion.

Its first goal is to vaccinate 3% of the people in these countries with a final goal of reaching 20%. It has signed a provisional agreement to buy AstraZeneca’s vaccine, which does not require storage in specialized ultra cold equipment like the Pfizer vaccine.

It is expected but not certain that less wealthy countries in Africa and South-East Asia, such as India, will receive vaccines at low or no cost under this program in 2021. Other countries such as those in Latin America may buy vaccines through COVAX. Several are also striking supply deals with drugmakers.

HOW MUCH WILL IT COST?

Vaccine makers and governments have negotiated varying prices, not all of which are public. Governments have paid from a few dollars per AstraZeneca shot to up to $50 for the two-dose Pfizer regimen. Many countries have said they will cover the cost of inoculating their residents.

Source – Thomas Reuters Foundation.

IN Egypt’s bustling capital people pack shops, cafes and public transport, many of them disregarding the rules that they should wear face masks in these spaces and keep one meter apart.

Official warnings about a second wave of coronavirus infections are widely dismissed.

Egypt’s first wave of COVID-19 subsided in the summer and restrictions on movement were gradually relaxed. Up to now, the population of more than 100 million appears to have been spared the surge in infections seen in European countries.

However, officially confirmed infections, which give a partial picture due to limited PCR testing and the exclusion of private test results, have risen slightly in recent days to about 350 daily cases, prompting the government to stress again the importance of mask-wearing and social distancing.

They face an uphill battle.

“When the government opened things up, people stopped being disciplined. Everyone became careless,” said Alaa Adel, a 26-year-old engineer buying a mask in downtown Cairo after forgetting to bring one from home.

“Everyone keeps their mask in their pockets, and once the policeman comes by or if they stop at a checkpoint, they wear it.”

The Egyptian health ministry could not be reached for comment on enforcement of physical distancing and other protective measures.

In March, airports, hotels, malls and cafes all closed, paralysing the vital tourism and hospitality sectors. Some restrictions on opening hours and capacity remain in place. Egypt responded with a stimulus package of 100 billion Egyptian pounds ($6.4 billion) to support its economy, where most are employed informally.

In a cafe in Cairo’s Moqattam neighbourhood, capacity is at a fraction of normal level, but only about half of the customers wear masks and hardly any follow physical distancing rules, said owner Mohamed Sabry, adding he is reluctant to challenge them.

“Poor people don’t care about these things. People live day by day.”

Despite the threat of 4,000 Egyptian pound ($255) fines for ignoring the rules, many in shops, public offices, buses and metro carriages still go bare-faced.

“People should be more disciplined. Most people don’t think about it, or do not understand how dangerous this disease is,” said a 45-year-old public servant Mohamed Mahmoud, one of the few customers wearing a mask at a café in downtown Cairo.

The government has confirmed a total of 111,955 cases including 6,508 deaths.

Source – Thomson Reuters Foundation.

IN Egypt’s bustling capital people pack shops, cafes and public transport, many of them disregarding the rules that they should wear face masks in these spaces and keep one meter apart.

Official warnings about the second wave of coronavirus infections are widely dismissed.

Egypt’s first wave of COVID-19 subsided in the summer and restrictions on movement were gradually relaxed. Up to now, the population of more than 100 million appears to have been spared the surge in infections seen in European countries.

However, officially confirmed infections, which give a partial picture due to limited PCR testing and the exclusion of private test results, have risen slightly in recent days to about 350 daily cases, prompting the government to stress again the importance of mask-wearing and social distancing.

They face an uphill battle.

“When the government opened things up, people stopped being disciplined. Everyone became careless,” said Alaa Adel, a 26-year-old engineer buying a mask in downtown Cairo after forgetting to bring one from home.

“Everyone keeps their mask in their pockets, and once the policeman comes by or if they stop at a checkpoint, they wear it.”

The Egyptian health ministry could not be reached for comment on enforcement of physical distancing and other protective measures.

In March, airports, hotels, malls and cafes all closed, paralysing the vital tourism and hospitality sectors. Some restrictions on opening hours and capacity remain in place. Egypt responded with a stimulus package of 100 billion Egyptian pounds ($6.4 billion) to support its economy, where most are employed informally.

In a cafe in Cairo’s Moqattam neighbourhood, capacity is at a fraction of normal level, but only about half of the customers wear masks and hardly any follow physical distancing rules, said owner Mohamed Sabry, adding he is reluctant to challenge them.

“Poor people don’t care about these things. People live day by day.”

Despite the threat of 4,000 Egyptian pound ($255) fines for ignoring the rules, many in shops, public offices, buses and metro carriages still go bare-faced.

“People should be more disciplined. Most people don’t think about it, or do not understand how dangerous this disease is,” said a 45-year-old public servant Mohamed Mahmoud, one of the few customers wearing a mask at a café in downtown Cairo.

The government has confirmed a total of 111,955 cases including 6,508 deaths.

Source – Thomson Reuters Foundation.